The NASA Moon Survival challenge has so much more to offer than most facilitators realise..!

Whether you know it as Moon Landing, Mission to the Moon, or the NASA Survival Challenge, there’s no denying the popularity of this team development tool.

It creates captivating images of space exploration, then brings people together to navigate a high stakes survival situation – far more exciting than some other team building exercises!

Here’s the thing, though.

This activity has so much more to offer than most facilitators realise. It’s quite likely that if you’ve done this activity in the past, you may have missed the point completely.

In this article we’ll explain just how much this activity has to offer.

Here’s what we’ll cover –

- What is NASA Moon Survival?

- Why most people are missing the point

- How to get more from the NASA Moon Survival challenge

- The virtual NASA Moon Survival challenge

- Potential limitations of the task

- The three best NASA Moon Survival alternatives

- NASA Moon Survival FAQs

Download your FREE NASA Challenge resources 👇

What is NASA Moon Survival?

NASA Moon Survival is a common team development exercise. It’s used by organisations to build teams and develop team working skills, as an icebreaker, and in many other contexts.

In the challenge, you’re part of the crew on a spaceship destined for the moon. Your original mission plan was to land near to a mother ship on the moon’s surface and liaise with the team there, but on the way, mechanical issues force you to crashland over a hundred miles from the rendezvous point. Your ship and many of your supplies were damaged in the landing, so it’s up to you and your team to decide what to bring with you as you attempt to make the journey on foot.

Here’s what you’ve got to choose from –

- A box of matches

- Food concentrate

- 50 feet of nylon rope

- Parachute silk

- Portable heating unit

- Two .45 calibre pistols

- 1 case dehydrated Pet milk

- 2 hundred-pound tanks of oxygen

- Stellar map (of the moon’s constellation)

- Life raft

- Magnetic compass

- 5 gallons of water

- Signal flares

- First aid kit containing injection needles

- Solar-powered FM receiver transmitter

You must rank these items in order of least to most important for survival, first as an individual and then as part of a group.

The proposed benefits of the NASA Moon Survival challenge

It’s claimed that this challenge can help you to achieve four things:

- Explore the fundamentals of effective team working

- Encourage group decision making

- Quantify a team’s effectiveness

- Explore the impact of training on groups’ abilities to make effective decisions

Let’s take a quick look at each.

Effective teamwork is crucial for any organisation, as harmonious teams achieve more and work more efficiently. Without guidance though, real teamwork can be very elusive. People are liable to argue on behalf of their opinion and experience frustration when this is ineffective, meaning the resulting conflict tends to result in either suppression of differences or capitulation to a minority to appease them: neither of which actually represent convergence of opinion.

The more divergent opinions are at the outset, the more difficult they become to reconcile.

In terms of quantifying team effectiveness, a ‘correct’ answer to the challenge was provided by the Crew Equipment Research Section of the NASA Manned Spacecraft Center at Houston, Texas. This means that for answers closer to the correct one, participants or groups have done objectively better.

Why most people are missing the point

Most facilitators only focus on the first three outcomes, with little or no attention paid to the final one: explore the impact of training on groups’ abilities to make effective decisions.

Left to their own devices, participants are prone to employ ineffective techniques which are not conducive to effective decision making. When used as an experiential learning activity, this is fine: everything that happens is valid, whether it’s people arguing, not listening to each other, or whatever else. The debrief then presents an opportunity to talk through the task, ask questions, teach people about how they behaved and why, and hopefully instil better behaviours for next time.

But beyond this context is where the NASA Moon Survival challenge shines. The activity was initially conceived as an experimental tool to explore the role and impact of structured guidance on effective decision making.

To best understand this, let’s take a look at the origins.

Where did the activity come from?

The original NASA Moon Survival task was created by Jay Hall, a doctor of social psychology who worked at the Graduate School of Business in the University of Texas at the time of its publication.

The task arose from social psychology research into group effectiveness, with the view to systematically improve the efficacy of team development exercises.

In 1970, Hall and Watson used the NASA Moon Survival task in a study designed to explore ways to reduce the confusion, frustration, and time-loss frequently associated with team group activities.

Here, 148 participants, all from middle and upper management roles in small businesses, carried out the task. Participants spent time together in their experimental groupings before the challenge took place in seminars and other sessions, leading to familiarity but not to close relationships.

Here’s the key difference between this version of the task and the one commonly used in business contexts:

The participants were split into experimental and control groups.

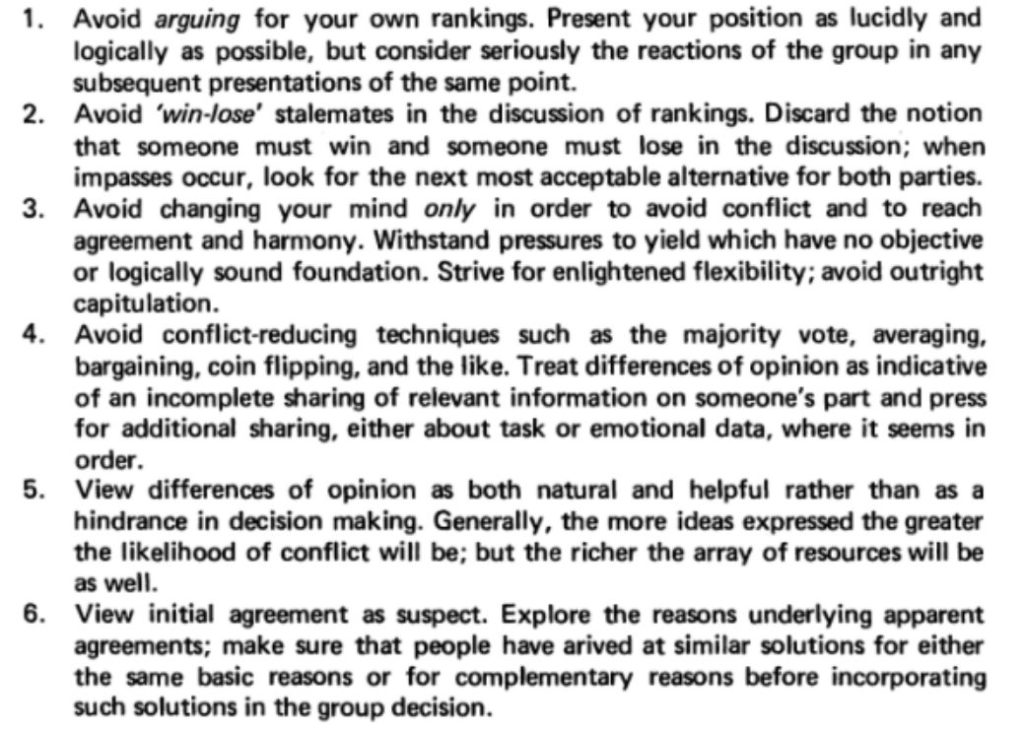

Control groups were briefed then left to their own devices.Experimental groups, on the other hand, received the following procedural ground rules. These were designed to orient groups towards working through conflict in a meaningful way, rather than defaulting to suppression of or capitulation to divergent opinion, as often occurs.

How to get more from the NASA Moon Survival challenge

Download your FREE NASA Challenge resources 👇

If you head to Google and type in “NASA moon survival challenge instructions” you’ll likely find something along the lines of the below:

- Ask individuals to rank the fifteen items in order of most to least important, with 1 for most and 15 for least. Ensure this is completed in duplicate.

- Collect one copy for scoring.

- Ask participants to join their discussion group to repeat the scoring. Each group must arrive at consensus.

- Compare group results with the correct answer.

These instructions, combined with a structured debrief and the right talking points, give facilitators everything they need to explore individual and group behaviours, and how these affect decision making.

Discussions can explore innovative and creative thinking, and incorporating the procedural ground rules into discussion after the activity is a good way to reflect on the types of behaviour that can improve teamwork.

With what we’ve just seen about how this activity can function in an experimental setting, here’s an expanded set of instructions for that context:

- Ask individuals to rank the items according to their importance.

- Collect one copy for scoring.

- Split your participants into teams, then split these teams into control groups and experimental groups.

- Provide the experimental groups with procedural ground rules.

- Ask groups to repeat the scoring. Again, each group must arrive at consensus.

- Compare group results with the correct answer.

- Compare the results of the control and experimental groups.

In this context, the activity provides enough data to explore whether or not guidance on how to work better as a team equates to better performance. By comparing the results of the experimental and control groups relative to the correct answer, you end up with a quantitative demonstration of the role of intervention.

For practitioners in academic contexts – think business schools, psychology departments and so on – the NASA Moon Survival challenge thus becomes an incredibly powerful activity.

The virtual NASA Moon Survival challenge

To maximise its value, the NASA Moon Survival challenge must be done in the way which fits best with the needs of the participants. This allows for powerful insights into group dynamics and, where relevant, a measure of how much group dynamics can be improved with the relevant interventions.

We’ve distilled all of this down into the MTa Immersion online NASA Moon Survival challenge, which you can find here.

In the virtual version data tabulation is taken care of behind the scenes, letting you focus on facilitating. While your participants progress through the individual and group tasks, here’s what you’ll be able to see:

- Results of individual versus expert rankings

- Results of group versus expert rankings

- Results of individuals versus groups

- The number of individual movements.

- The number of group movements.

The virtual NASA Moon Survival challenge allows for both experiential and experimental versions of the activity to take place. Facilitators looking to develop teamwork within their organisation have access to the task and accompanying materials to guide constructive discussion.

People working in experimental settings are able to collect and tabulate data from control and experimental groups, and export this for processing in a range of statistical analysis software.

Potential limitations of the task

While Hall & Watson’s study is from 1970, Hall’s original writeup on the NASA Moon Survival task is variously cited as 1962 or 1963. Whichever of these dates is correct, something interesting stands out:

This was written before the moon landing.

It wasn’t until 6 or 7 years later that Neil Armstrong took his famous first step onto the lunar landscape, meaning the public’s understanding of the moon and its conditions would’ve been completely different to ours.

This isn’t just a point of interest, either. The different level of baseline knowledge may actually reduce the efficacy of the activity, for one key reason:

Divergent opinions are a prerequisite of a good group activity.

Will our increased understanding reduce the distance between participants’ opinions when completing the task compared with people in the 1960s and ‘70s?

The three best NASA Moon Survival alternatives

While powerful, the NASA Moon Survival challenge isn’t appropriate for all situations. Depending what you’re looking to achieve, the three tools below may be better suited to your needs.

Sandstorm

One limitation of the NASA Moon Survival challenge, even when implemented correctly, is that the judgements it requires are fact-based rather than value-based.

Imagine if instead of deciding which items are best suited for survival, you had to decide who would live and who would die in an emergency situation. Should the investor get a seat on the rescue helicopter? His oil fortune is funding the project, after all… Or should the young photographer with a small child waiting back at home take his place?

Value-based exercises often generate more controversy, potentially equating to more enthusiastic involvement from participants. By incorporating these judgements, participants can learn more about what drives different behaviours.

The Culprit

In this activity, participants play the role of top detectives tasked with solving the toughest cases. The latest murder case requires effective collaboration to solve, and the pressure is high.

While evaluating clues and trying to solve the case, participants explore and improve their ability to work in a team. The activity offers great opportunities to increase self-awareness, build trust, and improve problem solving: all crucial skills in the modern workplace.

The Culprit is available online via MTa Immersion, or as a physical experiential learning kit.

Survival! Exploration: Then and Now

This lesson plan provided by NASA builds on the moon survival challenge by asking students to look for commonalities required for survival in very different time periods.

In one session they’re asked to survive in a new settlement in Jamestown in 1607. As a pioneering colonist a long way from home, your survival considerations may feel quite different to a stranded astronaut!

While the learning outcomes here focus less on team development and more on the commonality of survival in vastly different contexts, the exercise provides an interesting demonstration of how potential limitations of the challenge can be addressed.

You can find the full lesson plan on the NASA website, here.

NASA Moon Survival FAQs

You or your participants will probably have more questions about the NASA Moon Survival challenge. We’ve rounded up a few common ones below.

Gravity is different on the moon, surely if there are 4-6 of us we can just carry everything?

This is a good question, and tricky to answer. Realistically, leaving a box of matches behind isn’t going to have any noticeable impact on the size or weight of the items you take, so why not bring them along just in case?

Just how the best fiction sometimes requires us to suspend disbelief, you may need to remind participants that the purpose of this activity is to foster teamwork and encourage reflection, rather than to pick apart the intricacies of the physical reality of trying to survive on the moon.

Why would astronauts pack matches in the first place?

Despite what we said earlier about the layman having a better understanding of lunar conditions than someone in the 1960s, some questions may arise from misconceptions about how certain things will function in space. If someone raises the point of whether matches would work on the moon, let them know that you can actually light a match in a vacuum: the oxidising agents in the match head will burn, but the stick won’t.

This question and others like it are great segues into discussions about creative implementations for items, too. Even if you couldn’t light a match, what other uses could you find for it? A makeshift splint to supplement the first aid kit, maybe? Or how about a way to draw straws for particularly unpleasant tasks that no one wants to volunteer for?

Part of effective facilitation for this activity is to get people thinking beyond their fixed mindsets, and questions like this are a perfect opportunity to do so.

What does [x] do?

The potential uses of the items on the survival list aren’t all immediately obvious. It’s likely you’ll be asked what certain things do. Some of the ones we get asked about most frequently:

- Parachute silk: this material may be able to shield survivors from solar radiation.

- Two .45 calibre pistols: while there’s no alien life to subdue on the moon, the pistols may make for a method of propulsion. How effective is up for the survivors to decide.

- Solar-powered FM receiver transmitter: participants nowadays may be less familiar with FM technology, so you could explain that the transmitter can send and receive messages to the mother base when there is a direct line of sight.

Developing the confidence to be a divergent and innovative thinker requires participants to justify their reasons for their rankings, so avoid giving too much information about what each thing ‘does’. Offering some context on the properties of more dated technology may be useful however.

Where can I find the original study that this challenge comes from?

The challenge was created by Jay Hall in 1962, sometimes cited as 1963.

The article referred to in this blog post is called ‘The Effects of a Normative Intervention on Group Decision-Making Performance.’ It’s by Jay Hall and W. H. Watson, and was originally published in volume 23 of the journal ‘Human Relations.’

You can find it on Google Scholar and various other academic databases, although some may require a paid subscription for full access.